What are the rules for probationary periods and federal employees?

What are the rules for probationary periods and federal employees?

By Drew Friedman

Editor’s Note: This story was updated to add clarification on where to find probationary status information on the SF-50.

After the Trump administration reminded agencies that federal employees on their probationary periods are the easiest to fire, some may be wondering about the specific rights of probationary feds, and where there may be exceptions or exemptions.

The rules around federal probationary periods gained more attention after a Jan. 20 Office of Personnel Management memo asked agencies for lists of all their employees currently on probation. OPM Acting Director Charles Ezell told agencies to “promptly determine whether those employees should be retained at the agency.”

Probationary periods for federal employees typically last for one year. In less common circumstances, certain agencies and federal positions require two-year, or even three-year, probationary periods. Generally, the longer probations are reserved for law enforcement officers and certain employees at the Defense Department.

Importantly, a probationary period is not limited only to new employees entering the federal workforce for the first time. Employees who move into the Senior Executive Service, for example, or those who take an extended break from working for the federal government before returning to work at an agency, will usually have to complete a one-year probationary period.

Jenny Mattingley, vice president of governmental affairs at the Partnership for Public Service, said probationary periods in the federal workforce don’t hold the same sometimes negative view they may have in the private sector.

“It’s really a trial period, if you will,” Mattingley said during a webinar last week. “With a private sector lens on, usually the idea of probation means you’re on a trial period, but maybe with a more negative connotation. In the federal sector, it means you’re on a trial period before various employment rights, like appeals rights, kick in.”

The OPM memo on probationary periods takes a “different approach” from how the employment status is usually handled at federal agencies, Mattingley said.

“Typically, probationary periods have been done internally — a manager or supervisor makes a determination about whether the employee on their team is going to pass the probationary period or not,” Mattingley said. “This is a very different approach in terms of sending those lists to OPM, and centralizing things over to OPM.”

There are several other caveats to keep in mind for the rules around federal employees’ probationary periods.

For one, federal employees partway through a probationary period who transfer to a different agency in many cases can count the partially completed probationary period toward the one-year total. Prior federal service typically counts toward a probationary period, as long as a break in service is shorter than 30 calendar days.

But it also depends on an employee’s exact position, said Debra D’Agostino, a founding partner of the Federal Practice Group, which specializes in federal employment law.

“If you’re essentially doing the same job that you were doing at agency A, and you’re now doing that at agency B, and there was just a week or two gap in between when you left agency A to start at agency B, then you can tack on your prior service at agency A to your tenure,” D’Agostino said in an interview. “But, for example, if you’re going to school to get a degree in something specialized while you’re working at one agency, and then you get a completely different type of job at another agency, you usually can’t tack on your prior service.”

Probationary periods and terminations

The difference between probationary federal employees and career federal employees becomes most apparent in cases where terminations are involved. On the surface, probationary federal employees don’t appear to have a lot of rights in the case that they are terminated, but there are some exceptions.

In contrast to career federal employees, probationary employees generally do not have the right to appeal a termination to the Merit Systems Protection Board — except in a few circumstances. Probationary employees can appeal their termination to the MSPB is if the termination was motivated by “partisan political reasons” or “marital status.”

Prohibited personnel practices are also still applicable for probationary employees — meaning terminating a probationary employee for a discriminatory or political reason is illegal. Additionally, if there is evidence that multiple employees are being targeted for partisan reasons, then there would be an ability to challenge terminations with a prohibitive personnel practice charge.

“That previously was rarely used, but that suddenly might be frequently used,” D’Agostino said. “If they do terminate multiple probationary employees, and it turns out that they all are registered Democrats, that’s certainly something that could be an issue, that they could appeal to the MSPB.”

Probationary employees, however, do not have “due process” rights, meaning an agency can terminate the employee with only a written reason for the termination and the date effective — which could be as soon as “effective today.”

In cases where a career federal employee past the probationary period is terminated, agencies are required to give the employee at least 30 days’ notice, the right to reply to the notice, and evidence against the employee on why they are being terminated.

“Usually what we see is that probationers are issued a piece of paper that says, ‘effective today, you are terminated, and here’s why’ — and oftentimes it’s something very generic. It doesn’t need to be the same type of reason that you would remove a career employee. It can be as simple as, ‘it wasn’t a good fit,’ or ‘we felt your performance wasn’t up to standard,” D’Agostino said. “They do have to put it in writing, but they don’t have to give any notice. They don’t have to give you any right to reply. They don’t have to give evidence against you. The vast majority of times, you just get a piece of paper saying, ‘effective today, you’re terminated from the government.’”

Federal employees who get promoted into the SES may also see some differences to the standard rules for probationary periods. New SES members are typically put on a one-year probationary period, but if there is a performance issue, SES employees sometimes get demoted back to the General Schedule, rather than being terminated.

How feds can figure out their status

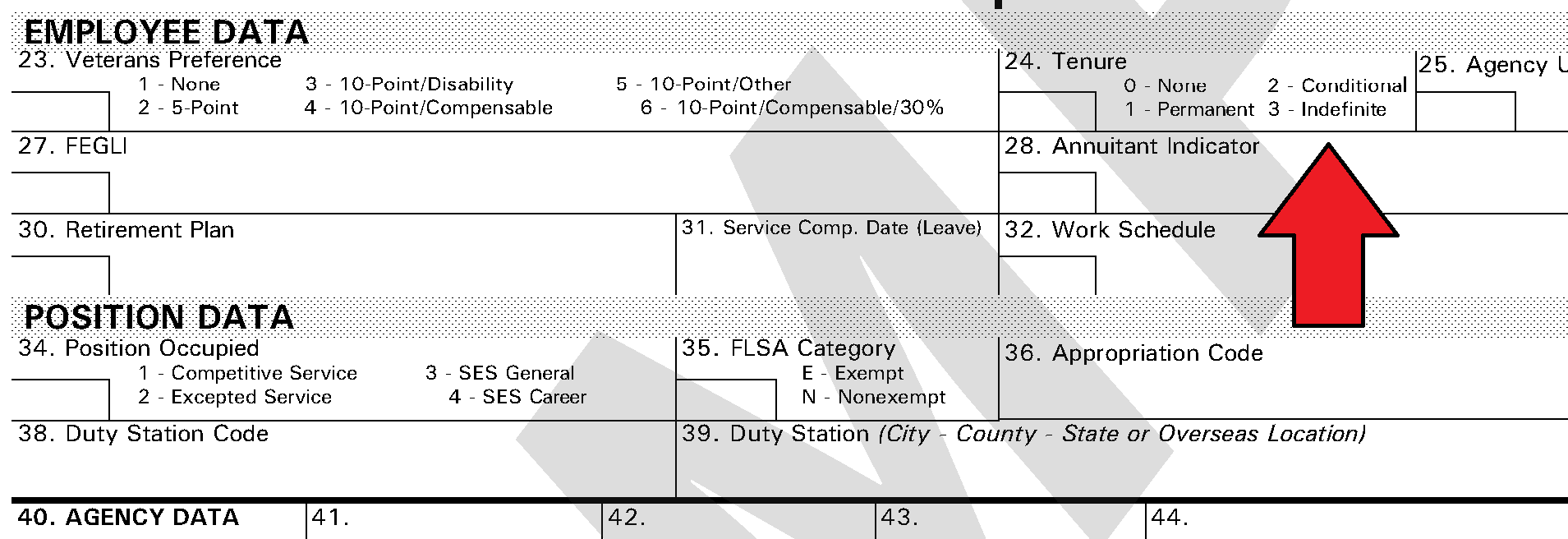

Federal employees who want to know their current status of employment, and whether they are a probationary employee or not, can start by checking box 24, titled “Tenure,” under the “employee data” section of their standard form 50 (SF-50). That section of the federal personnel form will typically note a number between 0 and 3, determining the federal employee’s tenure status.

An employee’s tenure status can depend on many circumstances, including what type of position the employee holds. But usually in box 24 of the SF-50, a “1” refers to a career federal employee who is not under probation. A “2” means the employee is in a “career-conditional” position, and would be probationary if they are still within their probationary period. Employees can check with their agency’s HR office to confirm their exact employment status.

Guidance from the Government Publishing Office offers further details on many of the various notations that might be found on the SF-50, and what they mean.

Federal employees may also find further information on their probationary status, and when their probation ends, written in the “notes” section of their SF-50.

D’Agostino, however, said she has seen many cases where agency HR offices have marked down the incorrect information on an SF-50 for an employee, marking them as an employee under a probationary period when they actually are not on probation. The errors often occur when an employee moves from one agency to another, and HR offices can sometimes be slow to record when the probationary period ends.

“We do see a lot of correction actions run to fix job tenure, because of mix-ups about what prior service counts and what doesn’t,” D’Agostino said. “If folks feel like that is wrong, now is certainly the time to go to HR to get that fixed. I think what’s critical right now is that every employee knows their status.”

Federal employees should also pull their electronic official personnel folder (eOPF) and make sure everything is accurate, D’Agostino added.

Full Source Here